Change requires changing your mind, mental models. How do you make up your mind? And how to facilitate this in a group. I developed this story in response to a question in Quora: Does the brain take steps to react in a linear fashion?

A brain doesn’t react, nor does a brain take steps; a living being does. To react doesn’t require a brain. I can refer to Newton’s Third law of Motion: action = -/- (minus) reaction. Any body exerting a force on anybody, exerts an equal force in opposite direction. Mass is the natural way a body resist change; that’s why we call a large group “a mass”: they resist change in equal force.

A body reacts to external triggers. Our body works also by (re)acting without bothering the brain, sometimes called reflexes or instincts. You may notice this while walking or riding a bike. These patterns of behaviour have been tuned to the perceived environment.

I once fell standing in a bus at the bus stop, because a bus next to us in the bus station started to drive. I saw it out of the corner of my eye, the windows of our bus were foggy, and my body “thought”, we moved, so reacted to the perceived motion. I fell in a standing bus. The other way around: you’ll get carsick, when driving and trying to read, as your body and brain process conflicting information.

Brain. An apparatus with which we think what we think. (Ambrose Bierce, The Cynic’s Dictionary (1906); republished as The Devil’s Dictionary (1911)). And we think in metaphors and not in language. For instance “a brain taking steps” is a metaphor. We speak metaphor. I’ll use your metaphor of taking steps, to illustrate how a brain works in a non-linear way.

Human beings mastered the art of translating metaphor into language. The funny thing is, that the word “trans-late” literally means “to carry over” as does the word “meta-phor”, over (meta) to carry (phora). They combine in a nice cycle of steps: ….–> metaphor –> translate –> metaphor –> …

Step 1: remember to recycle

Step 1. A brain also works in cycles, recycles, step by step. A brain reacts on reactions by “remembering” the action-reaction cycles of the body. Please notice the use of “member”, a synonym of “limb”.

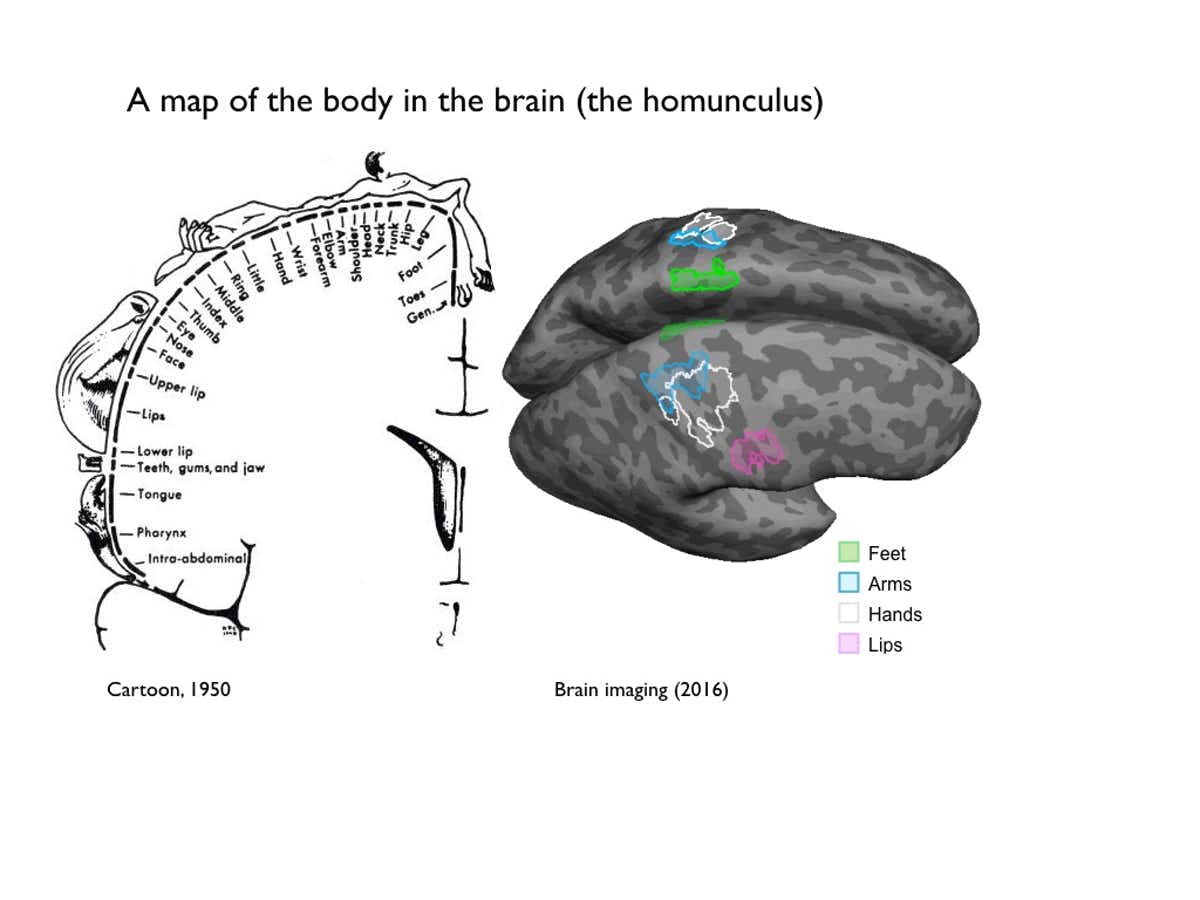

Every part or member of your body is represented (or recreated) in your brain and these parts “remember” the motions (that’s why we use the metaphor “emotion” when the feeling has been translated into “motion”). This works through feedback cycles of neuronic activity. In a way, they emulate the cycles in the body. The brain/nerve system structurally couples to the body system. You cannot separate the two.

Every part or member of your body is represented (or recreated) in your brain and these parts “remember” the motions (that’s why we use the metaphor “emotion” when the feeling has been translated into “motion”). This works through feedback cycles of neuronic activity. In a way, they emulate the cycles in the body. The brain/nerve system structurally couples to the body system. You cannot separate the two.

Step 2: invent a future

Step 2. And now the tricky part: based on past experiences, a brain (re-)creates the future of a next step. As she – I assume a brain is female – “knows” or remembers the cycles, a brain can induce next steps. – Automatically, as a response. In a way, the brain projects the next steps or frames of a cyclical movie on the situation. Using past experiences, you “know” what to expect.

A brain “invents” or “feeds forward” the future. Freeman, in “How Brains Make Up Their Minds”, (I’ve got a signed copy of the book!) calls this an intention. We are intentional beings. The intentions seem to come from our brain, but they’re just repeated or remembered actual “steps”.

Step 3: check the future against reality

Step 3. The next step (sic), the body/brain system checks the intentions with the actual situation. If they match, no problem. Back to step 1, the neuronal cycles are reinforced. They grow into “habits”, patterns.

If they don’t match, “Houston, we’ve got a problem”. Then the body/brain both reacts to it and learns.

Step 4: adapt the cycles

Step 4. The body reacts by trying to find balance. These reactions triggers (I don’t want to use “informs”, as there is no actual exchange of information) the brain cycles and creates, based on the perceived gap, changes in the brain cycles. So, as I told, I fell over in a still standing bus. Much to the amusement of others.

The differences between intentions and actuality “make” the cycles adapt, or “learn”. Please be aware, that I’m using metaphor. As intentional beings, we tend to read intentionality in every situation. I consider this a by-product of our thinking and not an attribute of reality. The universe, as I like to say, doesn’t care. It makes sense to assume there is a goal, purpose or meaning, because sense-making frames a situation. On the level of neurons and brain, they’re just cycling through action-reactions. As Step 5 shows.

Step 5: re-sume cycles

Step 5. Also, very strange at first, after some time, the adaptation in the brain cycles disappears. Freeman has shown this in very interesting experiments. The “old” or “previous” cycles reappear, and now generate “the same pattern” as before. The patterns do not stay “changed”, which we assume. They revert back to the original patterns.

Here we have to distinguish between the working of a brain and that of a computer. An image or experience is not stored in the brain. There is not “an illustration” or “a picture” of a computer in your brain, nor are their neurons labelled “computer type”. A networked network “remembers” through shifting patterns. As I wrote somewhere else, a brain works like a symphony orchestra. In a way, the violins (and cello’s, and flutes,…) just start repeating a previous theme. This is why we like music so much. Off course, the neurons involved don’t “know” this. But we’re back at step 1.

Side step: giving birth to unlearning

Side step: Interestingly, we need the pains of a mistake, error or loss, to induce producing neurotransmitters to “unlearn” previous cycles of behaviour, in order to remember (learn) new ones. Training, by the way, also makes use of “unlearning” neurotransmitters: exhaustion produces a “high” not unlike some drugs.

Freeman shows how all these processes produce oxytocin, a neurotransmitter which enables neurons to make new connections through – paradoxically – destroying existing ones. As a metaphor, oxytocin gives birth to new cycles and stories. As we’ll see …

The purpose of language is to remember the future

Now in most animals – living creature with a brain -, the experiences of the “mistake” are forgotten. They may have scars, but they cannot remember their causes. Only that they sometimes stop or wait, based on the situation. They’ve learned or adapted.

As we’ve invented language (I think it’s more because of inventing tools, but that’s another story. In a way, tools to throw improve the ability to project into the future. I do seem to remember written about it on this website), human beings are able to “remember” their past.

who do you think you are?

Our brains duly recycles the cycles of experience through stories. You may notice, that your brain seems to produce a stream of consciousness, never ending stories (or dreams). So we tell stories, histories, over and over again, because else we forget who we are and don’t know where to go.

Off course, another metaphor: a body “knows” who (s)he is. You are who you are, like it’s what it is. A body is always in the Here and Now. The brain may mediate between past and future. You may just get confused through the meta-cycles of neurons: brain activities somehow “aware” of brain activity. Planning for the future induces self-awareness. Get a mind and get a self for free.

As I wrote earlier: a brain produces the future, using “models”. What happens in reality encodes neural activities, these activities tune-in on each other and decode into actions, also called “realising”. (Based on Robert Rosen – Life Itself – I’ll delve deeper into this later). The brainy models-in-use adapt through the body – also a model – to real reality.

Long story short: inventing and using (throwing) tools induced developing metaphors, which in turn enables developing languages, digital communication and a sense of self.

Step 6: Change metaphor

Step 6. We’re re-remembering the future from our past. We both adapt to new situations and – unlike other animals -, remember the conditions and can condition others not to make the same mistake. As we’ve invented language, writing, printing, computers and now – voilà – internet.

By using our brain and language, we can exchange metaphors. With written language, we can exchange metaphorical messages without being present. My bet is, that many people were against inventing writing, because it would spell the end of story telling and remembering. With a printing press, we can start sharing on a wide scale. And nowadays, well, look around. But this didn’t change the way our brain works. We just shifted thinking about how she works.

A brain doesn’t work linearly, but cyclical, a bit like spirals, arabesques. The cycles are interlocked: there is no beginning and no ending. They develop themselves, in response to triggers from the outside. The cycles “behave” inside their own environment, closed off from the outside. They create and maintain a model of their environments – it can be proven -, to which they’re structurally coupled.

A brain differs from a computer as a fish differs from a ship. The latter we shaped (that’s why I used the very word “ship”), while the first created itself. A brain is not a machine, nowhere near.

Human beings can now go back to Step 1 and (after some thousands years of recycling) “step on the moon”. The next steps may be of interest to facilitators.

Step 7: interfering with change

Step 7. Now here comes the role of a facilitator or catalyst: in educating a group of human beings into new behaviour – or “change” -, telling someone what to do or not to do, will not be enough. Nor having the same intentions or a common vision of the future. Change means action, interaction.

Step 7. Now here comes the role of a facilitator or catalyst: in educating a group of human beings into new behaviour – or “change” -, telling someone what to do or not to do, will not be enough. Nor having the same intentions or a common vision of the future. Change means action, interaction.

Stories don’t work like programs, nor like algorithms. Stories do not resemble software. Stories work as heuristics, invented inventions. They’re lengthy metaphors, modelling real life situations. Stories “change” and we change, as we change our stories. And this involves recognizing “loss”.

As intelligent animals, we still need to experience experiences, the physical, “exercise”. We have to “work-through” emotions. So we call our meetings a “work-shop”.

Our body produces oxytocin, to change the cycles of thoughts in our brains. Brains “resist” producing oxytocin, as if she “knows” it will change her. So in facilitating we have to mix body work with brain work and thinking and feeling with (inter)acting.

Sometimes, this works through emotions, letting people express resistances. Sometimes through hard work, exhaustion. Sometimes through playing, role-play, simulating or constellations. Strang as it may sound, we have to forget our remembering, step over our losses, accept “defeat”.

Here is another good way to produce oxytocin: laughing. Having fun, playing, eating together. Irrationality, playing the fool actually enables change by promoting the bonding hormone. Off course, this is not yet an acceptable way in rational organisations. We’ll have to frame it as “serious play”.

Implementing other behaviour, other cycles of remembering, has to happen immediately after the release of tensions. A facilitator accepts the “negative” emotional feelings, expressing resistance, letting go, channels these into realizing – re-enacting -, other intentions.

So, I structure a session like a story. Starting with a prologue, individual work. Then looking for support, mentors, creating some first results. Then we dive into the deep: uncertainty, doubts, ambiguity, let’s say VUCA. As we reach the “counter point”, the dark, the unknown, tensions grows. A facilitator supports the development of tension. Big changes require big tensions. Then we get to turning point, the point of “letting go”. Here we usually meet the dark aspects of change: anger, fear, jealousy, sadness.

Then we pass through, somehow finding what somebody called “the goat path”. Or not. That’s all right too. Some times it takes more time, then we expected, fooled by our brain. In the end, I try to establish a new framing of the old patterns.

Change works best in small steps in the right direction

At the end of a session, I ask participants to write down what they intend to do differently tomorrow. Better to take a small step in the right direction, then a big one in the wrong.

Then I ask them: “if you don’t do that, or if it doesn’t work, what could you do then?”. In this I way, I prompt them to pre-evaluate their tensions between intentions and failing, defeat. I’m using the ability of the brain to predict their future. In doing so, I might prevent snapping back to previous, inadequate behaviour with changing actual behaving.

Just a loose remark: the price we pay for being able to put a man on the moon (‘a small step for man, …’) is remembering our losses.